November 2nd, 2020"The most important peacemaking agenda that we have now": Indigenous justice

An interview with Be it Resolved editors Esther Epp-Tiessen and Steve Heinrichs and graphic designer Matt Veith

Be It Resolved: Anabaptist & Partner Coalitions Advocate for Indigenous Justice, 1966-2020 is a new publication from Mennonite Church Canada and Mennonite Central Committee. The near-500-page anthology is a compilation of over 90 documents that detail commitments Anabaptists have made to Indigenous justice and decolonization.

In our latest interview, co-editors Esther Epp-Tiessen and Steve Heinrichs, along with graphic designer Matt Veith, share their encounters with the commitments, the challenge to the live up to some of them and what a book like this means for the church now.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why is this book important now?

EET: It's important to know where we come from, what our story has been, what our relationships have been. Looking back doesn’t mean getting stuck in the past. It enables our past to guide our present and our future. I do think it is important to keep on returning to the story and reinterpreting it to come to a deeper and a more faithful understanding.

Mi’kmaw-Acadian theologian Terry LeBlanc tells a wonderful story that illustrates this. A grandfather and grandson are walking through a forest. Every now and then the grandfather stops and looks back and then carries on. The little boy is worried. He says, "Grandfather, where are we going? We are going to get lost.” The grandfather replies that he is looking back so that he will know how to return home. It’s a beautiful story about the role that history plays in our self-understanding. We look back so that we can move forward in a good way. Sometimes that means having to repent for actions and understandings that have been harmful.

SH: We've forgotten the work that we've done in the past and the commitments we've made. I think if we are more mindful of our history it can help us act in the present in ways that actually respond to the priorities of Indigenous Peoples, and that work towards our own healing. I think we need this history to be faithful.

MV: I get the sense that the memory of migration was near to the Mennonites who made these commitments. They were much closer to a history of upheaval that brought them to a new place, put their lives through a blender, a process where they relied on their faith a lot, believed that God was with them and calling them to better things. Reading this book now during COVID-19, I feel it’s coming at a good time. As Mennonites we're all being forced to think about how our structures work, how we relate to our communities and how our communities are meaningful. We're in a moment where redemption could come from the malleability of some of these structures. I find it fascinating and meaningful that this book is coming out now.

In the introduction, Ruth Plett from Mennonite Central Committee describes the anthology as radical because it has the capacity to foster change but also takes us back to our roots. She says, “It’s radical because it’s actually nothing new. We have been making statements about commitments to Indigenous justice for years now; what we need to do now is turn those words into works—the costly action that attends to Indigenous calls and priorities.” What's been challenging about that process, about going back to the roots?

SH: It was tempting to just skip over the 1966 resolution that advocates for the adoption of Indian and Métis children. I know, love, and respect the people that were involved in forming that resolution. It’s also challenging to see what Stan McKay (former moderator of the United Church and Woodland Cree from Treaty 5 who writes the foreword for the book) says is the “colonial mindset at work” in your own community and in your own self. Indigenous Peoples will see a colonial mindset at work more often than I see it when I'm reading this. I confess, in my excitement about the justice matters this text addresses, I likely miss some of the problematic stuff.

EET: One of the things that struck me is that the statements and commitments do not represent a linear progression of enlightenment. It's not like we start at 1966 in kind of a colonial way and it just gets better and better and better. That's not the case. Some of the most profound documents come from the 70s and 80s in terms of the radicalness of the commitment. This is a reminder to us to return to that root and to continually ask ourselves, what are the blinders in front of us and what's the colonial mindset within each of us, even as we strive to be in solidarity?

SH: In recent years I think there has been a regression and we acknowledge that in the context paragraphs that precede some of the statements. We've taken a few steps back when it comes to our advocacy for self-determination, land reparation and so on. A danger with this book is seeing it as a non-critical celebration of Mennonite church bodies—“Wow, look at the churches!” It's not that. It is about pockets of the church and at times the church collectively responding in faithfulness to the cries of Indigenous Peoples that move the church to action. The ongoing struggle is to flesh out something more than words and a papered response.

Some of the most profound documents come from the 70s and 80s in terms of the radicalness of the commitment. This is a reminder to us to return to that root and to continually ask ourselves, what are the blinders in front of us and what's the colonial mindset within each of us, even as we strive to be in solidarity?

What documents or commitments were particularly meaningful to you?

EET: The letter by MCC in 1987 and the resolution by the Conference of Mennonites in Canada in July 1988 over the low-level flying over Innu land are particularly poignant for me. As a 30-year-old MCC board member I went to Labrador in 1988 at the height of the action. I watched the trial of Elizabeth Penashue and some of the other grandmothers who were arrested because they were walking on the runway to stop the flights.

SH: I didn’t know that!

EET: Yeah, I was there! I met Elizabeth Penashue for the first-time. I also like the letter of support written in 2008 by Lindsay Mollins-Koene from MCC, relating to the school system in Attawapiskat. That one is powerful because it responded to actions taken by the youth of Attawapiskat. They needed a new school and launched this amazing social media campaign and Shannon Koostachin, a 13-year-old girl, became the face and voice of that struggle. I love that MCC responded to the initiative of Indigenous young people.

SH: That highlights an important point. With pretty much each one of these pieces, we can point to Indigenous initiatives, groups and political organizations who called the church to action, from the mass Indigenous movements calling Canadians and faith communities to respond to the 1969 White Paper, to the 2018 statement by Mennonite World Conference in response to the Wounaan in Panama, who struggled to stop Settlers from taking their lands.

For me, I am blown away that Ike Froese in 1969 is talking about reparations. Walking in solidarity with Indigenous Peoples, where material concerns are at the centre, it's not simply about becoming more educated and aware so we can understand each other. It's actually shifting the material and structural realities we inhabit. Yet to talk about land and reparation is hard to do in the church.

I love the 2000 statement from the Canadian Ecumenical Jubilee Initiative (housed at the Canadian Council of Churches) because there's so much beautiful, biblical material in it. It's a well-crafted piece about the moral imperative of land reparation, of adequate land-base for Indigenous Peoples. Also, the 1995 Reconciliation Proclamation by the Sacred Assembly. It was a wide diversity of churches (mainline and evangelical) and even inter-religious representatives—Hindu, Muslim, and so on—that were there. That's unique.

I'm curious about how the work has affected you personally and what insights you've gathered for where our Body is headed together?

EET: For me the work has confirmed the sense that this is the most important peacemaking agenda that we have now. This and the climate. I feel a personal call to this work and the project has confirmed that.

The book highlights the official statements and documents produced by our institutions: Mennonite Church Canada, Conference of Mennonites and MCC. But what about individuals, groups and local congregations? So much of what will give this authenticity is if commitment and learning and actions of solidarity are born out in those settings. My question is, do institutional statements come alive in the responses of ordinary people, ordinary churches, ordinary followers of Jesus?

SH: Amen to that.

A significant response I had was one of great hope and gratitude. I continually came away amazed. I wanted to tell people how profound and beautiful these commitments are and was encouraged by the conviction of those who have come before us. I also feel the gravity of these statements. They’re like the Gospels, profoundly beautiful but deeply challenging. I feel great responsibility bringing this forward as someone who works within an institution. How can I play my part in facilitating follow-through on some of the commitments we've inherited?

Dave Courchene Sr. talks about the power that the church has to be a force for social change. I think we underestimate the ability and capacity that we have, even as a small Mennonite church community, to do wondrous things in solidarity with Indigenous Peoples. What's going to show that we genuinely care? The challenge for us is to run the kind of risks that Indigenous Peoples are running to change their material situation for the better. When we as a church read this, we should be lovingly unsettled by the Spirit to say we're being called to great things.

I’ll share an example of what this could look like. Last year, Canadian Mennonite University and Sandy Saulteaux Centre exchanged sacred bundles as a sign of their relationship. Sandy Saulteaux Centre gave CMU a two-row wampum to say this is a covenant that binds us—a sacred symbol. CMU shared a copy of the Martyr’s Mirror. It doesn't get more sacred than that. Now that is huge.

EET: Wow.

SH: My knees tremble at that. Are we willing to run those kinds of risks? Living into these commitments will provide opportunities for costly discipleship. If it's beyond words, if it's really fleshed out as a community, it demands a lot. As MWC put it in their resolution, it’s "disarming the structures of oppression.” It's a big challenge.

I think we underestimate the ability and capacity that we have, even as a small Mennonite church community, to do wondrous things in solidarity with Indigenous Peoples. What's going to show that we genuinely care? The challenge for us is to run the kind of risks that Indigenous Peoples are running to change their material situation for the better. When we as a church read this, we should be lovingly unsettled by the Spirit to say we're being called to great things.

MV: The work of discipleship in one's life and in a community is to keep revisiting. The hope I have is that this process of stopping and looking back to move forward feels like an act of discipleship, a rhythm in a community's life. I hope congregations and Christians take the storytelling around this stuff more personally and seriously, that they consider it part of the work we're trying to do of remembering, marking these milestones. I see that as a natural continuation of the work that this book is trying to do.

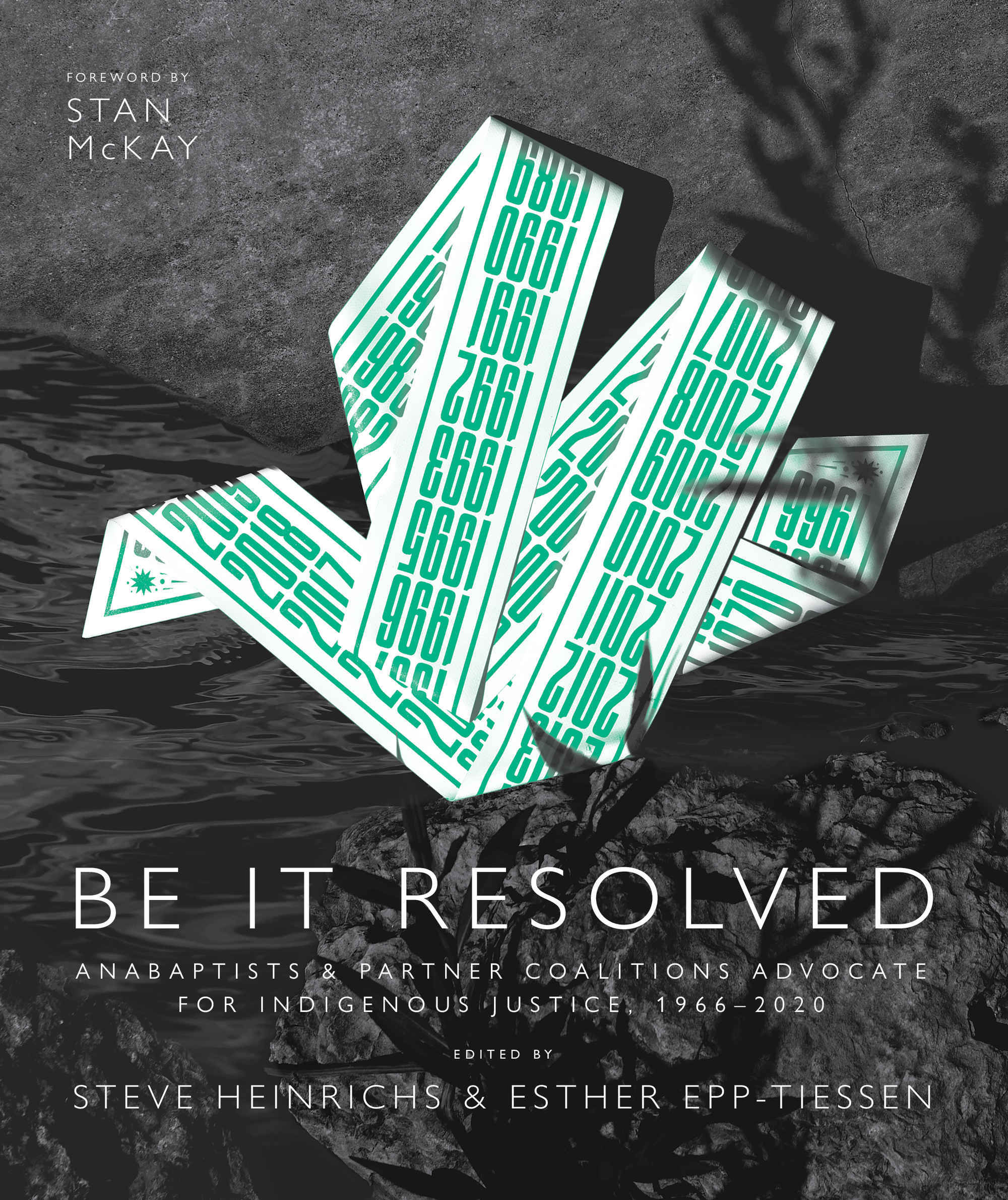

What was the inspiration behind the cover of the book?

MV: We thought about the theme of ribbons and wampums. I thought we could lay the wampum in the form of a dove but then we thought that would be insensitive. We would need to honour protocols and ceremony around those objects, but the idea of folding something into the dove stuck around.

The dates are on ticker tape folded into a dove, which is an image of peace. In the Mennonite imagination it's also the placeholder for what we think of as our common history, our peace tradition. I thought it was appropriate to do something like this because you communicate that the symbol is made up of something. In this case it's made up of these dates.

I physically printed the paper and tied it together and folded it, making a number of different arrangements. The concept of the cover is the very first fold idea I had. I took the ribbon I mocked up and had a physical vinyl ribbon printed from a print shop. It’s an indestructible vinyl that is waterproof. I folded it and took pictures of it in different places on the riverbank. The final version of the picture was taken under the Louis Riel footbridge in the rocks on the riverside. I chose that particular photo because there's a shadowing on the bird. There's a beauty to it but it also looks forlorn.

I’ll also mention that the book is printed in two inks, exclusively: black and green. The two colours are playing off of two focuses in history. One is what is happening in the mainstream world broadly speaking and the other is what Indigenous Peoples fight for and resist. Typically, when you print colours you have to mix them to get to the colour you want. But when you use a specific pre-mix of ink you're committing to that colour completely. What that means is that the colour that we used to denote Indigenous voices is at full brilliance. It's not distilled from different things; it's one colour and it's as strong and as brilliant as the black that runs through the book for the source documents. That second colour is completely brilliant and not a reduction of other colours.

Anything else?

SH: The book begins with Stan McKay and it ends with Wet'suwet’en. Stan mentions the ecological crises that we're in and Wet'suwet’en is both a jurisdictional fight and a fight for creation. We have two critical peacemaking issues—Indigenous self-determination and the ecological crisis— to address here and they're interrelated. I pray this anthology would be a resource for congregations and broader networks to leverage risky discipleship. I don't mean everyone on the frontlines. Some of us—yes. But also more savvy congregational engagement on local ecological justice. We need to keep in mind the words of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which says we have less than 10 years to address the ecological crises that we're in. I know it seems like doom and gloom, but I don't think we should ever tire of reminding ourselves of the significant place in history that we're currently in.

To purchase or borrow a copy of Be it Resolved, order at CommonWord.