August 28th, 2024Politics throttles Mennonite church relations with China

Winnipeg — A forty-year thaw of political relations between North America and China is freezing over again, throttling Mennonite church-to-church relationships that have been carefully nurtured in that time.

Leading up to 1979, a thirty year-long climate of mistrust, isolation and closed doors prevented bridge building. That same year, J. Lawrence Burkholder, president of Goshen College, and the Sichuan Provincial Education Bureau, signed their first exchange agreement heralding a new era of connection between Chinese and North American Mennonites.

Mennonite colleges, high schools, mission agencies and Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) enjoyed academic and religious exchanges for the next forty years. Hundreds of Chinese and North American Mennonites became friends. Goshen, EMU, and Bluffton became familiar names and places at many universities across Sichuan Province. English teachers from North America serving with Mennonite Partners in China were coveted by schools in China (MPC is a program of Mennonite mission boards and MCC).

Mennonite colleges, high schools, mission agencies and Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) enjoyed academic and religious exchanges for the next forty years. Hundreds of Chinese and North American Mennonites became friends. Goshen, EMU, and Bluffton became familiar names and places at many universities across Sichuan Province. English teachers from North America serving with Mennonite Partners in China were coveted by schools in China (MPC is a program of Mennonite mission boards and MCC).

When the covid pandemic reared its head in 2019, China closed its doors, ending exchanges with North America, including with Mennonites. Accusations about the origins of the virus quickly accelerated on both sides of the Pacific, creating tensions that remain.

Today, political news in North America routinely portrays China as a nation bent on world domination. The situation in China is similar; North America is blamed for everything that’s wrong with the world.

Myrrl Byler, retired director of MPC, said that in the 1980s and 90s, North American Mennonites were excited to live and work in China.

He first went to China in 1987, and was in the country during the violent protests in Tiannemen Square in 1989. He has over thirty years of experience with Mennonite exchange in China, and is writing a book about it. Titled Crossing the River by Feeling for Stones: Mennonite Engagement in China 1901-2020 will be published later this year.

Byler says the environment in China is radically different now compared to the years he lived in China. During a recent month-long visit there, he only saw “… a handful of Western faces, far fewer than when I first went to China in the 1980s.” Moreover, “Today, interest in even visiting China has almost vanished,” he said, adding that Chinese friends and colleagues corroborate his observations.

A former Chinese government official who was instrumental in assisting MPC, shared a poignant moment with Byler during his recent visit. “His young granddaughter came home from school and called Americans ‘evil demons.’” The slur reminded him of attitudes from the 1960s and 70s.

Academics and the Protestant church community feel acutely the loss of MPC and the connection it offered with the West. Increased control and supervision by government authorities make it difficult for Mennonite visitors from North America to freely interact with Chinese believers.

Jeanette and Todd Hanson worked in China from 1991 – 2015. Since 2019, Jeanette has continued to visit China in her role as director of Mennonite Church Canada’s International Witness program. She concurs with Byler’s experience of the political chill and its effect on church-to-church relations.

Both registered and unregistered churches in China are experiencing increased tensions as officials clamp down on freedom to conduct worship and normal church activities. Byler’s recent visit to China excluded attendance at church services or formal meetings with pastors. He worried such attention would alert officials and put his Chinese hosts at risk.

Byler says that “The vast majority of Chinese citizens seem content with their lives and what the government provides for them. They feel the government’s surveillance technology and information-gathering methods keeps their cities safe, unlike the violence in American cities that they see on the news. Few if any cities in the West can compete.”

The Chinese public largely accepts the narrative they are given about the world stage, and that the U.S. is behind nearly every event or decision in the outside world with which it disagrees, whether that’s the war between Russia-Ukraine or in the Middle East.

But with a population of 1.4 billion in China, the proportion of citizens who are not content represent a significantly minority, said Byler. Among the strongest opposition are some pastors and academics, ethnic minorities and persons on the fringes. “The exodus out of China during the past few years is noticeable in other countries,” he said.

Chinese people with money buy apartments and land in countries like Thailand and place their children in international schools. “In the past two years more than 100,000 Chinese have crossed into the U.S. illegally and sought political asylum, although the U.S. is now attempting to repatriate some of these persons to China,” said Byler.

The exodus among the general population of Christians, including pastors, has been particularly significant, according to Byler. This leaves many Chinese congregations without adequate leadership, but the reasons why some church leaders are leaving is understandable.

He’s heard from pastors with heightened fears of arrest and imprisonment, and pastors being stripped of their positions in the church and placed under investigation. The strain of constant surveillance, increased presence and involvement of government officials in churches and seminaries, and concern about families and children takes a heavy toll. Some pastors personally know peers who have been arrested.

Hanson notes that the church is no longer growing like it did in the 1990s and early 2000s. “Attendance in Chinese churches I connect with has not rebounded since the easing of Covid restrictions” she said. However, she’s heard that many leaders associated with Mennonite agencies and schools in the last past few decades remain with their congregations and are committed to weather the shift, just as their mentors dealt with difficulties in earlier times.

While active exchange between China and North America ceased in 2019, there is a large mainland Chinese diaspora in North America with whom the church can connect, says Byler.

“Many ethnic Chinese churches in the West, several of whom relate to Mennonite conferences, are experiencing growth via people who are leaving mainland China.” Byler said that North American anger directed at ethnic Chinese immigrants is “… an opportunity for our churches to be present, listening, supporting and advocating for those who have chosen to live in North America.”

As China increases its global footprint and influence, engagement with Chinese people also represents an opportunity for Mennonites world-wide.

“Mennonite pastors and churches in Southeast Asia and parts of Africa are interested in establishing ties to their brothers and sisters in China,” said Hanson. Pastors from the Meserete Kristos Church in Ethiopia have been in conversation with church leaders from China, discussing common concerns and looking for opportunities to assist each other economically.

Byler says that while some government powers try to isolate China, he hopes that ordinary people will recognize there is little to gain by distancing themselves from the world’s second largest economy. Meantime, North American exchange students at Chinese universities have been replaced by thousands of young people from across all of Asia, Africa and even South America, he said.

With more than forty years of history in China, Mennonite church agencies and schools have a renewed opportunity to be a bridge for those who see the importance of remaining tied to and supportive of churches and pastors in China.

Crossing the River by Feeling for Stones: Mennonite Engagement in China 1901-2020, written by Myrrl Byler, will be published later this year and available at Masthof Press or on Amazon.

-30-

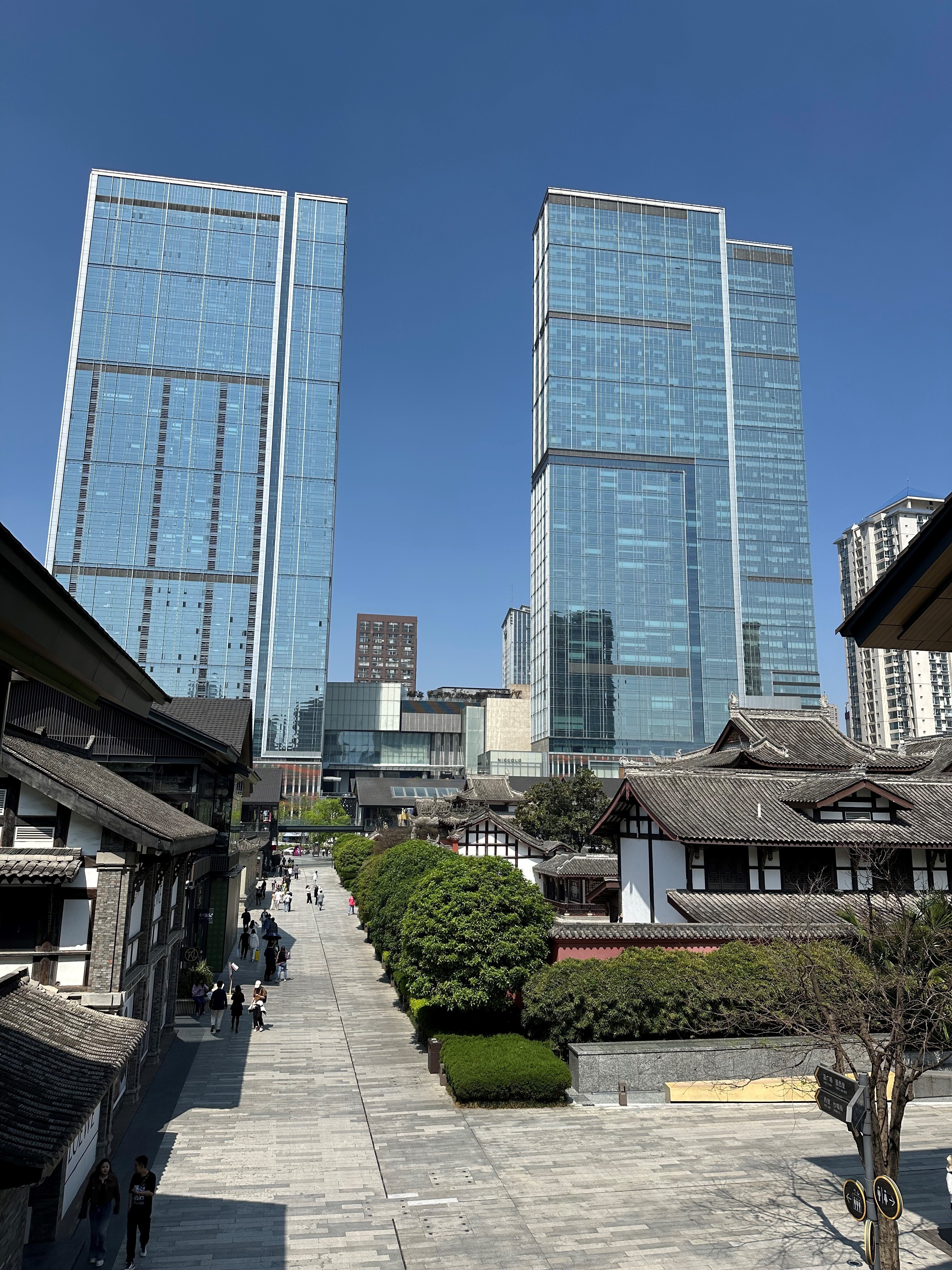

Photo: Cities all over China blend the modern and the traditional. In this scene from Chengdu, modern office towers are inter-planted with traditional Chinese architecture, which in this case are stores for western brands such as Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and high-end restaurants. Photo by Myrrl Byler